Let’s Incentivize Clinical Practice Again (ICPA)

Let’s Incentivize Clinical Practice Again (ICPA)

The U.S. healthcare workforce problem is routinely misidentified. Burnout and moral injury are real experiences, but they do not explain observed behavior. What is occurring is labor exit. Physicians and nurses are leaving direct patient care because the system no longer supports sustained participation.

This is not speculative. Physician labor force participation has declined even as demand for care continues to rise. Early retirement, reduced clinical hours, and movement into nonclinical roles are now common across multiple specialties. Nursing turnover remains elevated despite aggressive wage increases. When higher pay fails to retain labor, the issue is not compensation alone. It is job structure.

The consequences are already visible to patients. Wait times are longer. Continuity of care is worse. Visits are shorter. Reliance on temporary staffing has increased, raising costs while reducing consistency. These are not quality improvements. They are adjustments made in response to a contracting clinical workforce.

The drivers are structural. Over the past two decades, healthcare delivery has consolidated rapidly. Independent practices have declined. Employment has replaced ownership. Decision-making authority has shifted away from clinicians toward administrative and payer-controlled systems. Regulatory and documentation requirements have expanded steadily, consuming a larger share of clinical time without increasing clinical output.

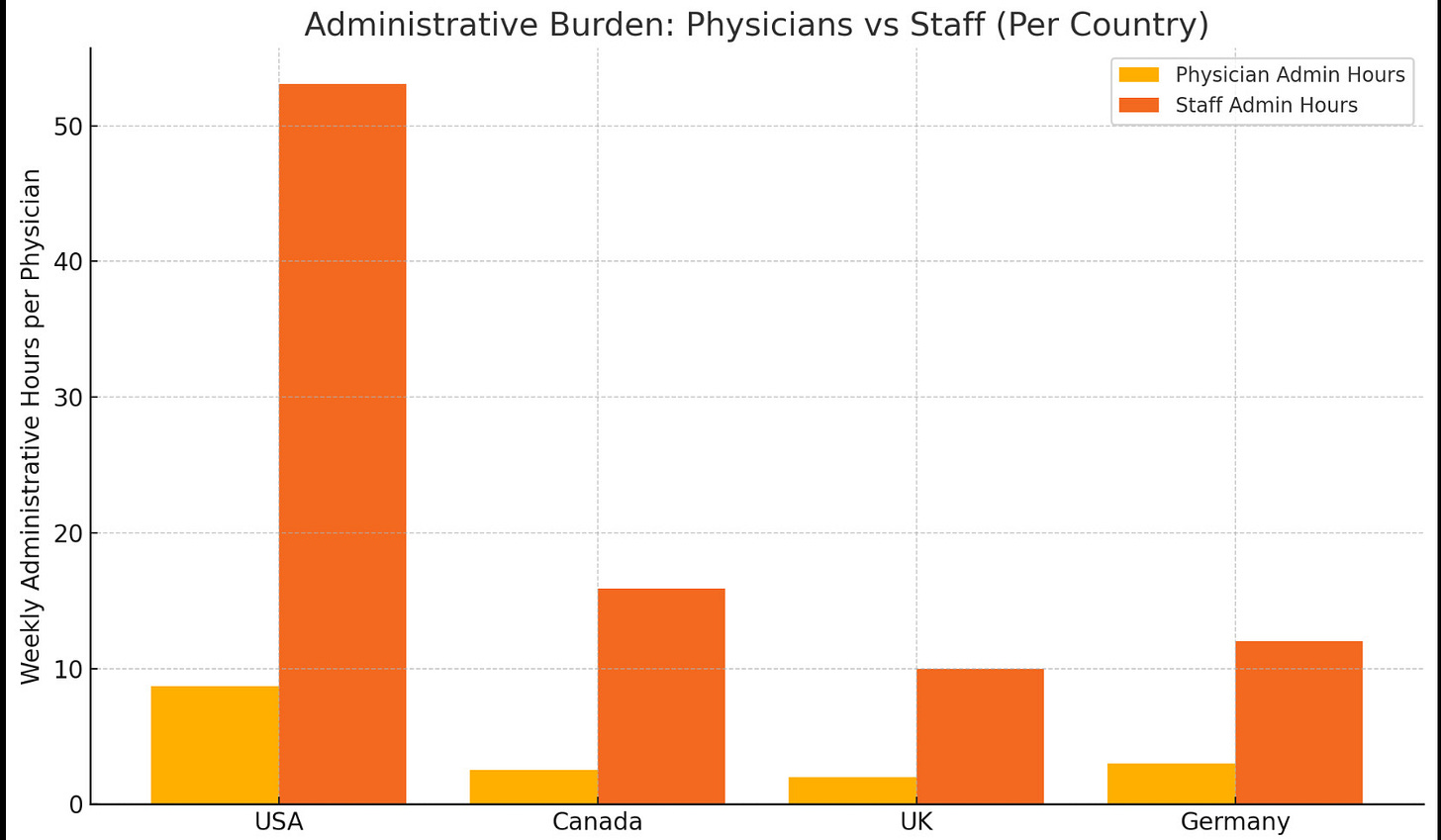

The growth of administrative workload has had a measurable effect on how clinicians spend their time. Multiple observational studies and national surveys show that physicians now spend a significant portion of their workweek on documentation, inbox management, prior authorizations, and compliance-related tasks. Estimates commonly place this burden in the range of fifteen to twenty hours per week, much of it occurring outside scheduled clinic hours. These hours do not expand access or increase the number of patients treated. They displace clinical work.

Nursing workflows reflect a similar shift, often to a greater degree. In many inpatient and procedural settings, bedside nurses report that documentation, order management, and administrative coordination consume a large share of their shifts. Time-motion studies have shown that direct patient care occupies a minority of total working time for floor nurses in some environments, with administrative tasks approaching or exceeding half of a typical shift. This redistribution of time alters the effective supply of care even when staffing levels appear unchanged.

Comparisons across countries reinforce this point. Systems differ in structure, but all require some level of administration. What varies is magnitude. In the United States, both physicians and supporting clinical staff spend substantially more time on administrative work than their counterparts in peer systems. When staff time is absorbed by documentation and coordination rather than patient-facing activity, physician productivity falls even if physician hours remain stable. Fewer patients can be seen per day. Clinical throughput declines without any reduction in demand.

Administrative hours also scale differently than clinical demand. As utilization rises, documentation and coordination requirements rise faster than patient-facing time. This creates a compounding effect. Each additional unit of demand consumes a disproportionate share of nonclinical labor, further reducing effective capacity. Systems respond by compressing visits, increasing patient-to-clinician ratios, and relying more heavily on temporary staffing. These responses raise costs and degrade continuity without improving outcomes.

From a labor perspective, rising administrative hours function as an invisible contraction of the workforce. Headcount statistics may appear stable, but effective clinical output per clinician declines. This amplifies access constraints, lengthens wait times, and worsens shortages without any corresponding decline in need. It also raises the marginal cost of remaining in practice, accelerating early retirement, hour reduction, and movement into nonclinical roles.

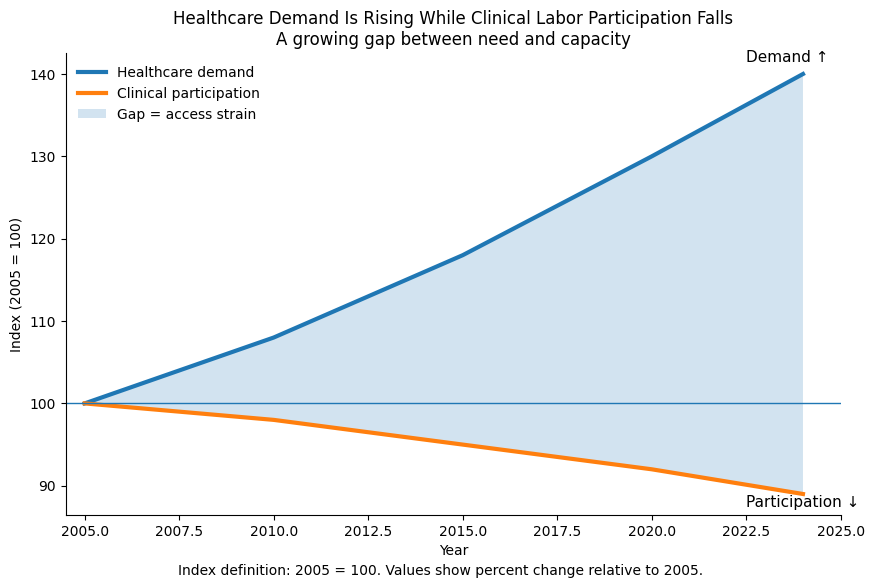

Demand is rising while clinical participation falls

The chart above illustrates the central structural problem.

Both lines are indexed to 2005 equals 100, which allows different measures to be compared on the same scale. An index value of 140 means roughly forty percent higher than the 2005 baseline. An index value of 90 means roughly ten percent lower.

Healthcare demand reflects population growth, population aging, and higher per-capita utilization. It is not spending and it is not insurance enrollment. It represents patients, visits, and clinical complexity. Clinical participation reflects physicians and bedside nurses delivering direct patient care, accounting for early retirement, reduced hours, and movement into nonclinical roles.

The widening gap between the two lines represents capacity strain. That gap is what patients experience as longer waits, compressed visits, more handoffs, and reduced continuity. It is not a temporary disruption and it is not explained by declining need. Demand has increased steadily. Clinical participation has not.

This divergence produces predictable effects. When fewer clinicians are available per unit of demand, systems compress visits, standardize care pathways, and increase reliance on temporary staffing. These responses raise costs and degrade patient experience without improving outcomes.

Burnout describes how individuals feel inside the system. Labor exit describes what they do in response to it. The charts show behavior, not sentiment.

None of this requires assuming poor intentions or bad actors. It reflects standard responses to attaching constraints to labor. When autonomy, mobility, workload, and financial agency are compressed at the same time, participation declines. Healthcare follows the same rules as other labor markets.

The baseline fact is straightforward. Demand is rising. Clinical participation is falling. Administrative time is expanding. Access and continuity follow participation. Any serious discussion of healthcare performance has to start there.