Why Medicalizing Social Problems Makes Them Worse

How Routing Social Determinants Through Healthcare Raises Costs and Weakens Community Solutions

Social determinants of health describe basic conditions of daily life. Housing stability, access to food, transportation, utilities, and neighborhood environment affect health outcomes. This has been understood for a long time. The shift occurred when these conditions began to be treated as services that healthcare systems should deliver rather than factors healthcare systems should account for.

Once that shift occurred, cost behavior changed.

When social services are routed through healthcare, they take on the characteristics of healthcare delivery. Documentation requirements expand. Coding becomes mandatory. Eligibility rules tighten. Vendor contracts multiply. Reporting obligations increase. Managed care logic applies. Consolidation concentrates control. The underlying service remains the same. The system around it becomes more complex and more expensive.

Recognizing a problem and delivering a service are separate functions. In healthcare, those functions were merged.

Over the past decade, CMS formalized this approach. The Accountable Health Communities model screened more than one million Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries for housing, food, and transportation needs. Medicaid Section 1115 waivers were used by states to pay for housing-related supports, nutrition services, and utilities through healthcare financing. Medicare Advantage plans added supplemental benefits covering meals, transportation, and home modifications. Some states allowed Medicaid managed care plans to substitute social services for medical care through “in lieu of services.”

Each policy change addressed a real pressure point. Combined, they moved social service delivery into the highest-cost system in the economy.

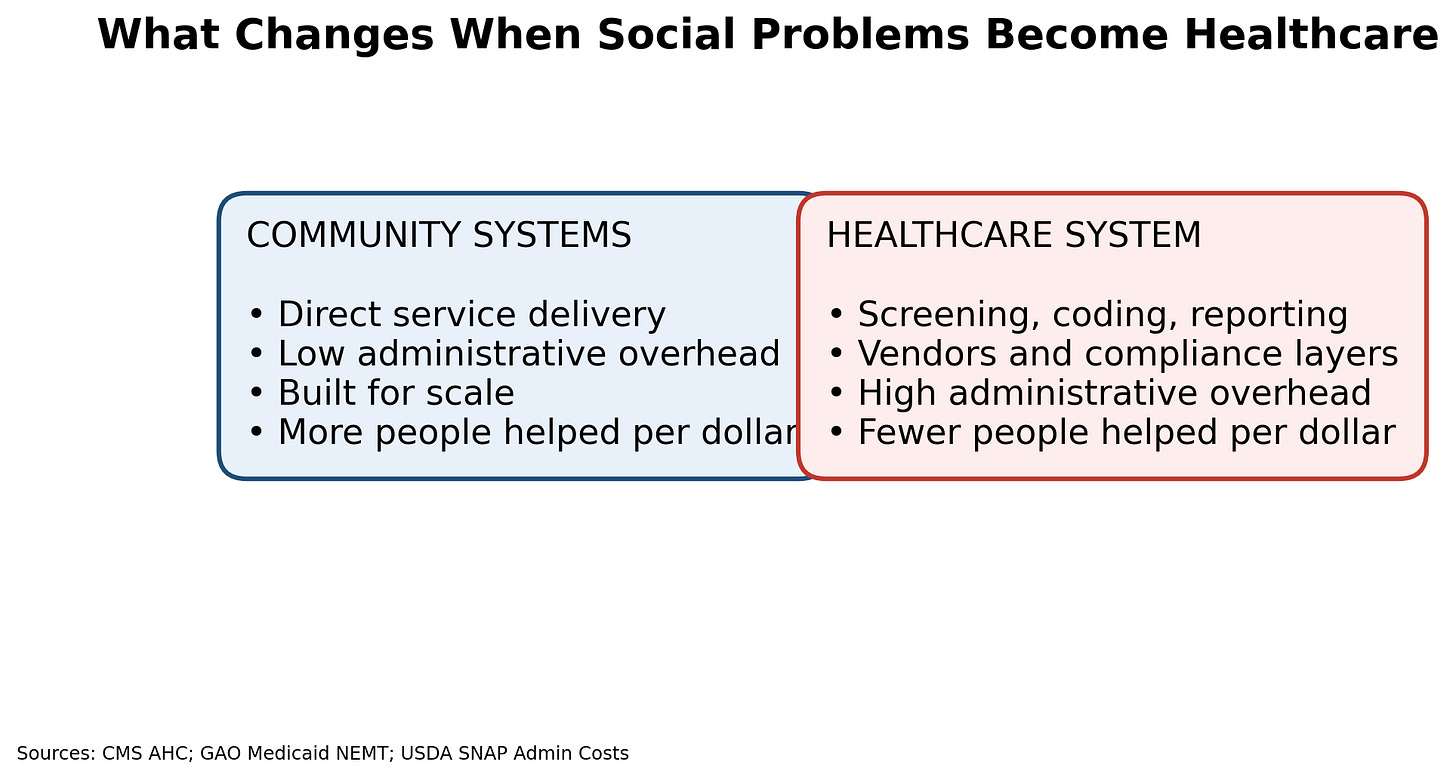

What Actually Changes When Social Problems Become Healthcare

Figure 1. What Changes When Social Problems Become Healthcare

When social services move into healthcare, the service does not change. The delivery system does.

Healthcare is built to manage regulated, high-risk, high-liability services. It is structured around billing, documentation, utilization management, and compliance. That structure exists to control clinical risk and financial exposure.

Community-based systems are structured differently. They are built to deliver basic services to large numbers of people with minimal friction. They prioritize access and scale. They operate with lower administrative overhead because they are not required to meet healthcare billing and compliance standards.

When social services are delivered through healthcare, they inherit healthcare’s structure by default. Cost increases. Access narrows. Friction rises. This follows directly from how the system is organized.

The Healthcare Cost Multiplier

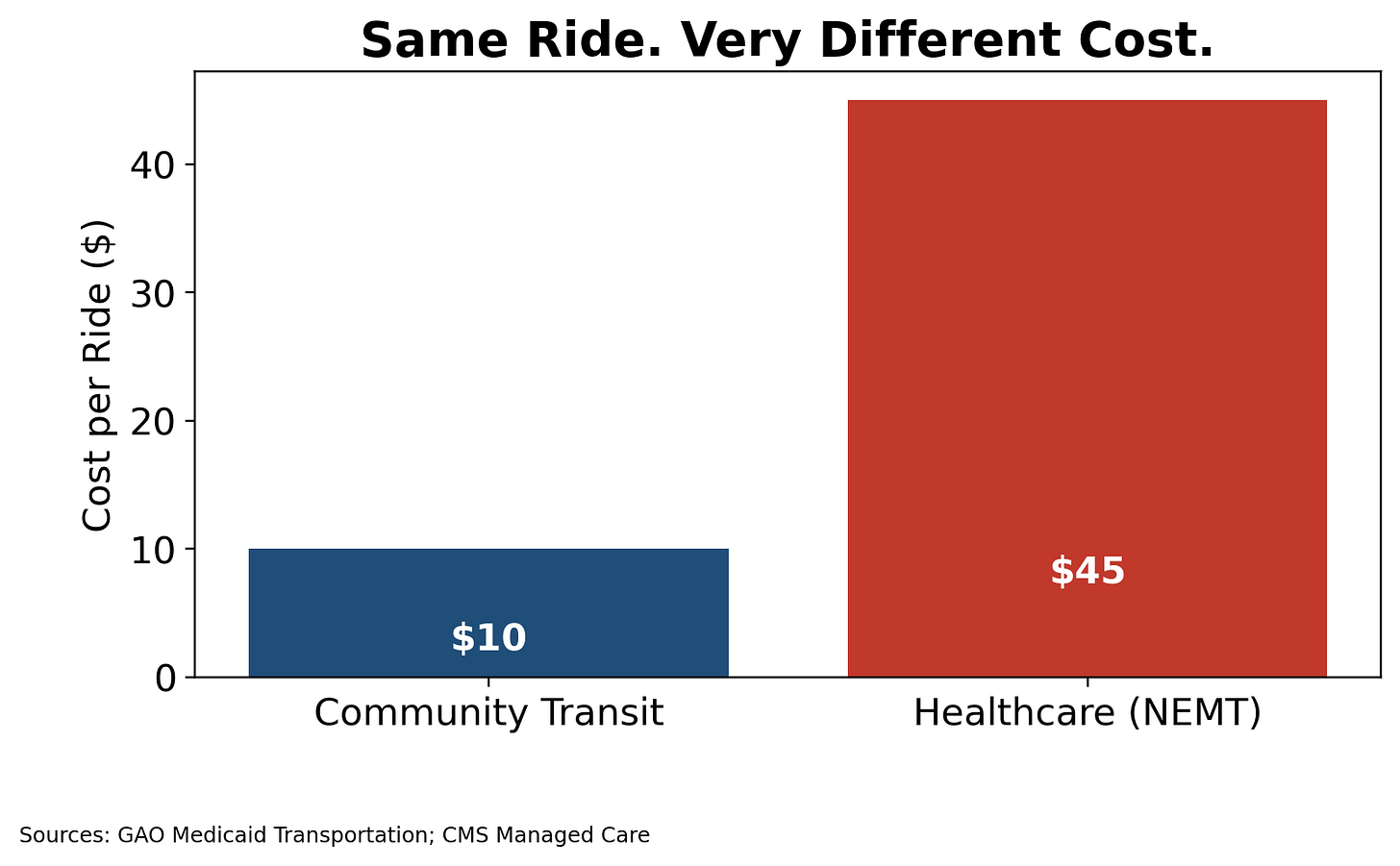

Transportation shows this clearly. Community transit programs and voucher systems typically cost five to fifteen dollars per ride. They move people efficiently and predictably. Medicaid non-emergency medical transportation frequently costs thirty to sixty dollars per ride.

The ride does not change. The passenger does not change. The destination does not change.

The cost difference reflects the system surrounding the service. Eligibility verification. Medical billing. Vendor contracting. Utilization review. Compliance oversight. Each requirement exists within healthcare delivery. None of them improves transportation.

Routing transportation through healthcare multiplies cost without changing the service.

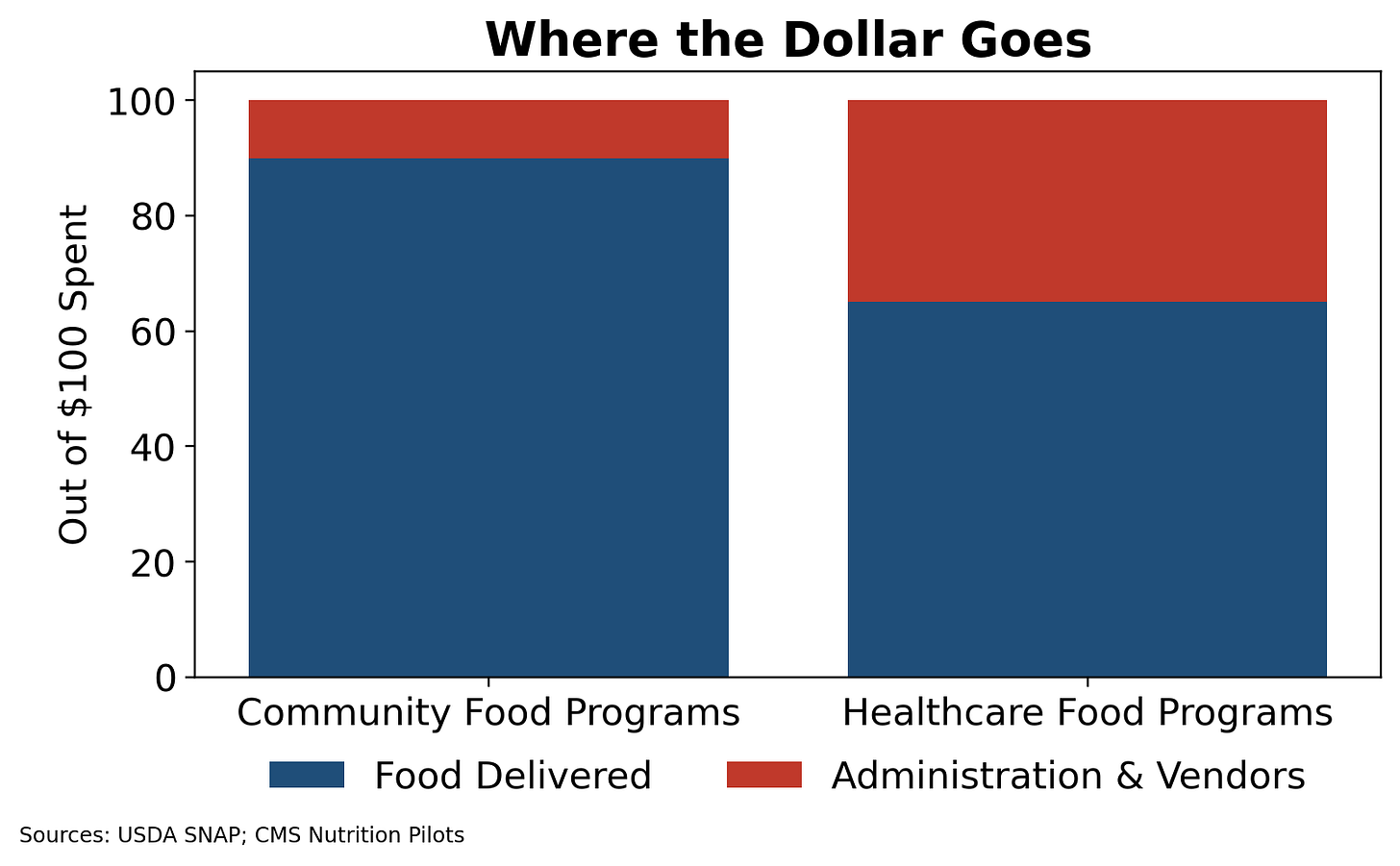

Food follows the same pattern. SNAP and WIC deliver food assistance with administrative overhead under ten percent. They are designed for population-scale reach. Healthcare-based food programs often carry administrative and vendor overhead exceeding thirty percent. Per-meal cost increases substantially. Reporting requirements expand. Eligibility becomes diagnosis-dependent.

The food itself does not change. The delivery process does.

Figure 3. Where the Dollar Goes

A larger share of spending shifts to administration when food is delivered through healthcare.

Housing illustrates the structural limit of this approach. Housing stability affects health outcomes. Healthcare financing now supports housing navigation, eligibility workflows, analytics platforms, and reporting infrastructure. In some programs, administrative spending approaches the value of the assistance provided.

Healthcare financing does not increase housing supply. Navigation does not create units. Documentation does not lower rent. The system becomes better at recording unmet need while remaining constrained by the same underlying shortage.

The Data Do Not Support Scale

Targeted social interventions can help individual patients. Evidence supports that at the individual level.

Evidence does not support scaling those interventions by delivering them through healthcare systems.

As programs expand, marginal benefit decreases. Administrative overhead continues to rise. Screening scales easily. Resolution does not. Early gains come from serving the highest-risk subset. As eligibility widens, each additional dollar produces less impact while system costs grow.

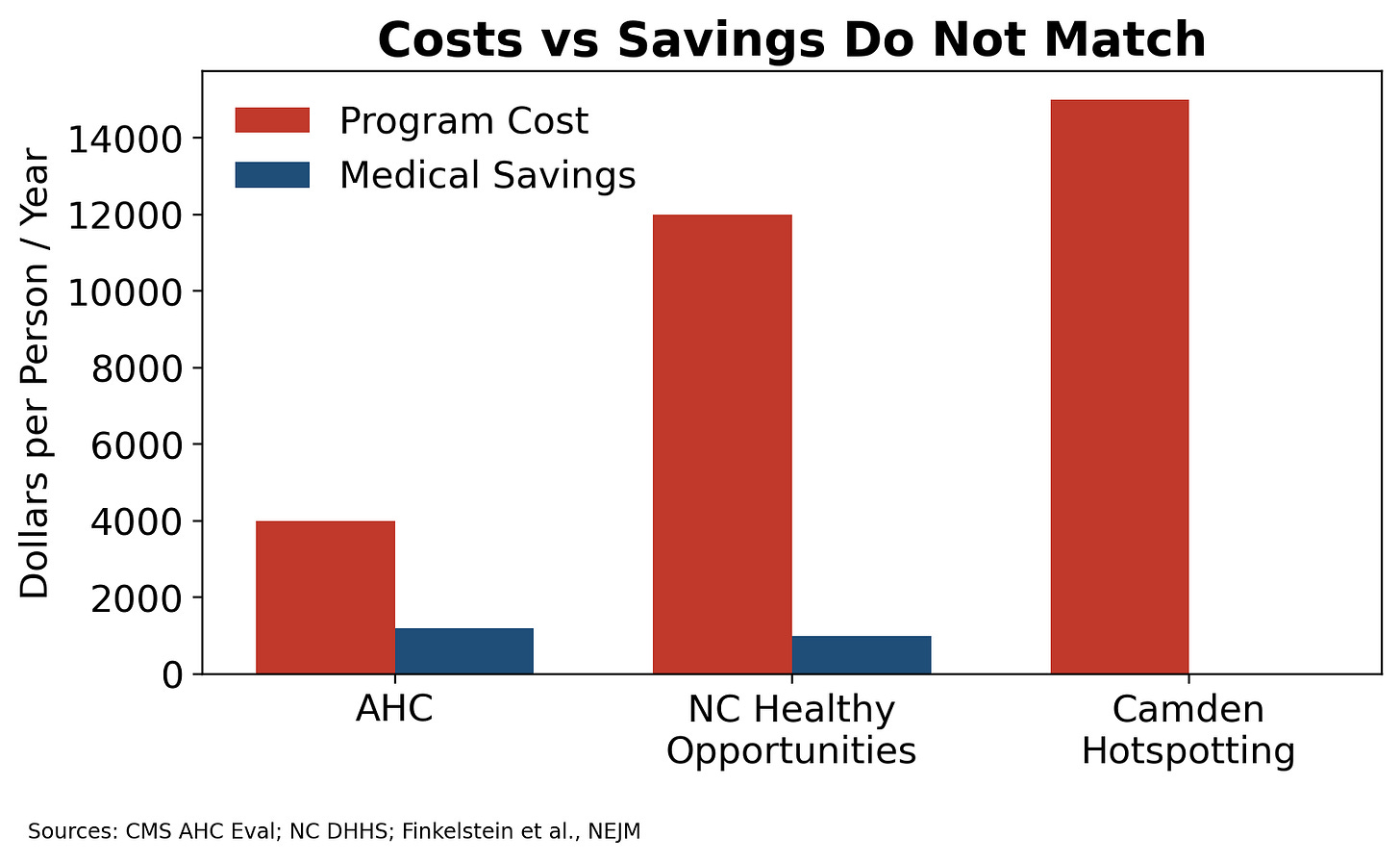

Figure 4. Costs vs Savings Do Not Match

Medicalized social programs do not reach cost neutrality at scale.

Large programs illustrate this pattern.

The Accountable Health Communities evaluation showed modest reductions in healthcare utilization with limited progress on resolving underlying social needs. Screening volume increased. Service resolution did not keep pace.

North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots are a Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration testing non-medical services related to food, housing-related supports, transportation, and safety. CMS authorized up to $650 million over five years, including funding for capacity-building infrastructure. At the two-year mark, North Carolina reported approximately $85 lower medical spending per participant per month, with fewer emergency department visits and some reduction in inpatient use. That figure reflects medical spending only, not net program savings after accounting for the cost of the social services themselves.

At least one academic analysis describes higher spending at enrollment followed by a lower spending trend over time. That pattern is different from demonstrating net savings or scalable cost efficiency.

Randomized trials of intensive social and care-coordination programs, including the Camden hotspotting study, showed no reduction in hospital readmissions once regression to the mean and control groups were applied.

Individual benefit does not translate into system efficiency when healthcare systems deliver basic social services.

Why Consolidation Makes This Riskier

As healthcare systems consolidate, the cost effects intensify.

Large health systems and insurers expand by adding service lines and administrative scope. Complexity increases revenue capture. Additional layers create billing opportunities and contractual leverage.

When social services are incorporated into healthcare, they become part of that administrative structure. Screening tools, referral platforms, care management teams, vendor networks, and reporting systems add cost regardless of service resolution.

This pattern has appeared in other areas of healthcare. Medicare Advantage risk adjustment. Home health services. Behavioral health carve-outs. Payment expanded faster than oversight. Documentation replaced outcomes. Consolidated entities captured revenue while performance lagged.

SDOH programs share similar characteristics. Screening is easy to document. Navigation is process-based. Outcomes are delayed and difficult to attribute. Payment is tied to activity rather than resolution. Waste becomes predictable even without explicit fraud.

Figure 5. Why Consolidated Systems Magnify Risk

Administrative expansion increases cost and weakens accountability.

Why This Matters

Cost increases do not remain internal to healthcare systems.

They appear as higher premiums, increased public spending, and tighter budgets. Employers absorb higher benefit costs. Public programs face tradeoffs. Fewer dollars remain for housing construction, transportation infrastructure, and food distribution systems that can operate at scale.

Medicalized delivery also changes access. Eligibility becomes tied to diagnosis, utilization history, and documentation. People with unmet needs but low current utilization receive lower priority. Support shifts toward crisis response rather than prevention.

Spending increases while coverage narrows.

Safety Nets and Delivery

Safety nets are necessary. The delivery mechanism determines how far resources go.

Basic services are delivered most effectively when friction is low and administrative overhead is minimal. Routing those services through a highly bureaucratic system increases cost, reduces reach, and slows access.

Housing, food, transportation, and utilities are better delivered through systems designed for scale. When these services are delivered through healthcare, cost rises and access tightens. Resources shift away from service provision toward management.

The Structural Problem

Healthcare was not built to deliver basic social services.

It was built to manage regulated, high-risk clinical care. When services that do not require that level of bureaucracy are routed through healthcare, cost increases automatically.

More paperwork. More eligibility rules. More vendors. More oversight. None of that improves the service. It increases friction and expense.

Healthcare can identify risk and coordinate referrals. When it becomes the delivery system for social services, cost inflation follows.

Social determinants of health identified the problem accurately but delivering them through healthcare increased cost and reduced reach.

Notes & Sources

This essay draws on publicly available federal evaluations, state Medicaid documentation, peer-reviewed research, and oversight reports. Specific sources are listed below by topic.

Social Determinants of Health (General)

World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health.

CDC / Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health Framework. These sources establish that housing, food, transportation, and utilities materially affect health outcomes.

CMS Accountable Health Communities (AHC)

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Innovation Center. Accountable Health Communities Model: Final Evaluation Findings (2024).

Over 1.1 million Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries screened.

Modest reductions in medical spending in navigation arms.

Limited evidence of large-scale resolution of underlying social needs

Medicaid Section 1115 Waivers (General)

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Medicaid Authorities and Options to Address Social Determinants of Health.

CMS. State Medicaid Director Letters on SDOH and Health-Related Social Needs. These documents describe how states use waivers to fund housing-related supports, nutrition services, and utilities through Medicaid.

North Carolina Healthy Opportunities Pilots (HOP)

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS). Healthy Opportunities Pilots Interim Evaluation Reports.

CMS 1115 Demonstration Approval for North Carolina.

Kaiser Family Foundation policy brief on NC HOP.

Key points reflected accurately in the article:

CMS authorized up to $650 million over five years, including capacity-building funds.

Reported ~$85 lower medical spending per participant per month at the two-year mark.

That figure reflects medical spending only, not net program savings after accounting for service costs.

Academic analyses describe higher spending at enrollment followed by a lower spending trend, which is distinct from demonstrating scalable net savings.

Transportation Costs

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Medicaid Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Oversight and Cost Analysis.

CMS Medicaid Managed Care guidance on NEMT.

These sources support:

Community transit/voucher costs typically far lower than Medicaid NEMT.

NEMT costs commonly reported in the $30–$60+ per ride range depending on state and vendor structure.

Food Assistance

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). SNAP and WIC Administrative Cost Reports.

CMS Innovation Center pilots related to nutrition and food-as-medicine.

These support:

SNAP/WIC administrative overhead generally under 10%.

Healthcare-delivered food programs carry substantially higher administrative and vendor overhead.

Housing-Related Services

CMS guidance on Medicaid housing-related supports (navigation, tenancy support).

HUD housing supply and affordability reports.

These sources support:

Medicaid funds housing-related services, not housing construction.

Navigation and case management do not increase housing supply.

Scaling and Cost-Effectiveness

Finkelstein et al., New England Journal of Medicine. Effect of Camden Coalition Care Management Program on Hospital Readmissions.

RAND Corporation evaluations of housing and super-utilizer interventions.

These studies show:

Targeted interventions may benefit individuals.

Large-scale healthcare-delivered social interventions do not reliably reduce utilization or produce net savings.

Consolidation and Oversight

U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Medicare Advantage enforcement actions and settlements.

Office of Inspector General (OIG). Medicare Advantage Risk Adjustment Oversight Reports.

GAO reports on home health and behavioral health billing.

These reports establish:

Administrative complexity, delegated vendor models, and weak outcome verification increase waste and abuse risk in consolidated systems.

Figures

Figure 1: CMS AHC evaluation; GAO Medicaid NEMT; USDA SNAP admin costs.

Figure 2: GAO Medicaid NEMT cost analyses; CMS managed care guidance.

Figure 3: USDA SNAP/WIC admin cost data; CMS nutrition pilot summaries.

Figure 4: CMS AHC evaluation; NC DHHS HOP reports; NEJM Camden trial.

Figure 5: DOJ, OIG, and GAO reports on Medicare Advantage, home health, and behavioral health oversight.

Closing Note

All figures use conservative ranges from government and peer-reviewed sources. No vendor-reported ROI estimates are used. Where reductions in medical spending are cited, they are labeled as medical spending differences, not net program savings.